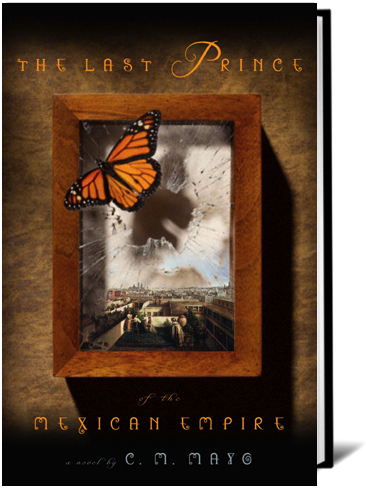

C.M. Mayo < Publications < The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire <

|

|

|

Article for ATENCION, San Miguel de Allende, February 2010, apropos of reading for PEN International San Miguel Center, February 16, 2010

The one Mexican date it seems the whole world knows is "Cinco de Mayo," which — take note, history aficionados— does not celebrate Mexico’s Independence or Revolution but the surprise victory of Mexican Republican forces over the French Imperial Army at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862. Nonetheless, the following year, the French took Puebla and then Mexico City, as well as much of the rest of the Republic. But Louis Napoleon’s idea was not to establish a protectorate North African-style; rather, a more elaborate and monumental scheme. With the support of a powerful group of Mexican conservatives, the Catholic Church, and a handful of European allies, a hosing of charm and, when needed, brutal threat, Louis Napoleon convinced Maximilian von Habsburg, younger brother of Austria’s Kaiser, to accept the throne of Mexico. Maximilian’s brief reign— he arrived in Mexico in the spring of 1864 and was executed at Querétaro in 1867— is one of the strangest and most fascinating periods in Mexico’s history. It is also one of the most challenging to comprehend, for it was a fundamentally transnational period. How to begin to make sense of an Austrian Archduke brought in to rule Mexico backed by the French Imperial Army? Whose previous experience was as Viceroy of Lombardi-Venetia? His wife, Carlota, was the daughter of the King of the Belgians, and her father an avid supporter of Louis Napoleon’s "Mexican Expedition." Carlota was also the first cousin of Queen Victoria, who did not offer the Mexican Empire military support but certainly, recognition and a very friendly ambassador. The Vatican, too, played a role, its position in part based on principle (the Republican government under Benito Juárez had confiscated Church property) and in part, crude political calculus (French bayonets protected Rome from a takeover by Italian nationalists). And what of the United States? Embroiled in the Civil War and then its aftermath, players for the Union and for the Confederacy had diverse and often conflicting interests in Mexico. One of Maximilian’s most unlikely and embarrassing involvements with Americans was when he, who had no children, took on as his Heir Apparent Agustín de Iturbide y Green, a two-and-half year old boy whose American mother, almost immediately upon signing the contract with Maximilian, changed her mind. When Maximilian refused to return her child, she went to Washington DC to meet with Secretary of State Seward and then all the way to Paris, to lobby John Bigelow, the U.S. Minister in France and arch-foe of the Mexican Empire. The courts of Europe, all closely interrelated, were abuzz with the scandal. Therein lies the story of my novel, which is based on many years of original archival research in Mexico, Europe, and the United States. Though the little prince might seem a curious footnote in history, I would argue that, as he was in fact the living symbol of the future of the Mexican monarchy, his story becomes a integral part of the story of Mexico itself, its struggle for identity amidst the wrangling for control of the Americas, this devastating chapter in the aftermath of Independence, and a prelude to the Revolution. |