|

Download

Reader's Guide as a PDF Download

Reader's Guide as a PDF

from Unbridled Books.

About

the Book

The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire is a meticulously researched, strongly

felt, and vividly rendered novel from history. It tells a story

that in its time was infamous, an international scandal, but

ended up lost, reduced to a footnote —literally, in one

accounting— to history. The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire is a meticulously researched, strongly

felt, and vividly rendered novel from history. It tells a story

that in its time was infamous, an international scandal, but

ended up lost, reduced to a footnote —literally, in one

accounting— to history.

As the author explains in the Epilogue to the novel, "The

Story of the Story," it grew from a "germ" so

perfectly Jamesian that she couldn’t have made it up if

she tried.

Having lived in Mexico City for several years and considering

herself to be relatively well educated and informed, fluent in

Spanish, Mayo came across a painting on the wall over lunch at

someone’s home, a portrait of a little English looking boy,

cradling a rifle, with Chapultepec

Castle in the background. When she asked, she was told that

the subject is Augustin

de Iturbide y Green, "the prince of Mexico." Astonished

by her ignorance of that period in Mexican history and understandably

intrigued by the notion of monarchy in the New World, she tried

for several months to find out more, to no avail, until she was

halfway through reading Jasper Ridley’s Maximilian and

J uarez

and came upon the chapter, "Alice Iturbide": uarez

and came upon the chapter, "Alice Iturbide":

My surprise at finding my

own countrywoman, long ago, at the apex of the Mexican aristocrac— both antagonist and victim,

motivated and blinded by who knew what medley of ambition, avarice,

love, borrowed patriotism or naiveté—so intrigued

me I knew at once I wanted to explore and expand the story into

a novel.

The core story is that during

the short lived Second Empire in Mexico, Emperor

Maximilian and Empress Carlota take custody of the toddler

son of a Mexican aristocrat and an American mother, grandchild

of the first Emperor of Mexico, to be their heir presumptive.

But in the way that novels have of doing, it took  on

a life of its own, and the story of two heartbroken parents trying

to get their little boy back from a callous pair of Royals growing

more unstable by the day as the French withdraw from Mexico and

their Second Empire comes crashing down around them, grew into

something much larger: an international story of political intrigue,

war and diplomacy that plays out in Mexico City, Washington,

D.C., England, Paris, and even Rome, that overlaps the U.S.

Civil War and tells of the complex border politics between Mexico

and the U.S., especially with the Confederacy, both before and

afterwards. on

a life of its own, and the story of two heartbroken parents trying

to get their little boy back from a callous pair of Royals growing

more unstable by the day as the French withdraw from Mexico and

their Second Empire comes crashing down around them, grew into

something much larger: an international story of political intrigue,

war and diplomacy that plays out in Mexico City, Washington,

D.C., England, Paris, and even Rome, that overlaps the U.S.

Civil War and tells of the complex border politics between Mexico

and the U.S., especially with the Confederacy, both before and

afterwards.

Most of all, The Last Prince

of the Mexican Empire is a novel about the very question

of what it would mean to be Mexican. Would the people of Mexico

be subjects, or citizens? Just as important, however, we learn

along the way how we historically, politically, and culturally

share so much more with our neighbor to the South than we commonly

think we do.

Lucky for us, Mayo decided that

the only way she could get at this question was to tell "an

emotional truth," and only the novelist has the tools to

do that, to explore the emotions and motivations of the characters

involved in the events of the narrative: the creative imagination

and what Mayo calls the use of "armchair sociology."

One such use is a fortunate consequence of her decision to tell

the story from multiple

points of view, including the multiple points of view among

the characters about

each other. They reveal themselves through their interactions

and gossip about the other characters, drawn from the letters,

journals, diaries, and other materials Mayo spent years combing

through and, best of all, we come to realize that some questions

are ultimately unanswerable— the essence of good writing.

Further, by recreating on the page the sights, smells and sounds

of Mexico City, Cuernavaca, Georgetown, Paris, and the novel’s

other settings, both outside and inside, Mayo is not just painting

a backdrop against which the characters play out the drama. Rather,

she creates a "virtual reality" for the reader to stroll

about in, to see things as the characters perceive and experience

them, including what they wear, where and why they wear it, how

they behave, and what they talk about, all of which serve to

carry the narrative.

Our noses tingle from the dust

in Doña Juliana’s parlor that coats the knick knacks

on the shelves, each of which tells us something about her personal

and political history. We positively taste Alicia’s strawberry

pies, for which she is famous, which remind us of her personal

history and values, and reinforce the bicultural nature of her

marriage and relationship with her husband.

Finally, by enabling us to see her characters within their particular

worlds, both public and private, to hear what they are saying

and how they are behaving about and to one another, we empathize

with them, create our own versions of them, and draw our own

conclusions about them, to better understand the larger and essential

meanings of the narrative.

About

the Author

C. M. Mayo was born in Texas in 1961

and grew up in California. Having written since she was a child,

Mayo wanted to start taking her writing seriously when she was

in her early 20’s, but didn’t know how to proceed.

She did study for a summer under Paul Bowles, in Morocco, but

after coming back found herself still baffled by "how to

go about being a writer," not to mention a little intimidated

by the "jumping off into the abyss" images of how she

would make a living as a writer. C. M. Mayo was born in Texas in 1961

and grew up in California. Having written since she was a child,

Mayo wanted to start taking her writing seriously when she was

in her early 20’s, but didn’t know how to proceed.

She did study for a summer under Paul Bowles, in Morocco, but

after coming back found herself still baffled by "how to

go about being a writer," not to mention a little intimidated

by the "jumping off into the abyss" images of how she

would make a living as a writer.

So she took the more practical path, earning her Master’s

Degree in economics from the University of Chicago in 1985, where

she met her husband, a prominent Mexican economist. After moving

with him to Mexico City, she taught international and development

finance in both the undergraduate and the MBA programs at ITAM,

a private university, and (as Catherine

Mansell Carstens) published two books on finance, before

turning to literary writing:

"I realize now that it's

tricky to start writing serious fiction until you are in your

30’s, anyway. I think that you have to settle down, and

have a sense of compassion for other people, which is what you

really need to flesh out fictional characters. Most people in

their 20’s are about "me" and to write fiction,

you have to come from a more spiritual place than that. And that

just takes a little time. So I went into economics, which has

its fascinating aspects, but for me, alas, not enough of them.

When I turned 30, I decided it was time to "fish or cut

bait": if I wanted to be a writer, I had to start taking

that seriously. I did some research, and found some good writers

conferences to go to, and just took it from there. One really

does have to educate oneself as a writer, and it’s not always

easy or obvious as to how to go about doing that; certainly it

helped that I was a little bit older."

C.M. Mayo started by writing short fiction,

and her first book, Sky Over

El Nido, won the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction.

Her second book, Miraculous Air:

Journey Of A Thousand Miles through Baja California, the Other

Mexico, is a widely-lauded travel memoir. It was written

at a time when Mexico was going through a major political crisis.

She undertook it to try to come to understand Mexico better,

"when all I wanted to do was to leave." An avid translator

of contemporary Mexican literature, Mayo is founding editor of

Tameme Chapbooks ~ Cuadernos, and has also edited the anthology

Mexico: A Traveler's Literary Companion,

a portrait of Mexico in the fiction and literary prose of 24

Mexican writers. C.M. Mayo started by writing short fiction,

and her first book, Sky Over

El Nido, won the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction.

Her second book, Miraculous Air:

Journey Of A Thousand Miles through Baja California, the Other

Mexico, is a widely-lauded travel memoir. It was written

at a time when Mexico was going through a major political crisis.

She undertook it to try to come to understand Mexico better,

"when all I wanted to do was to leave." An avid translator

of contemporary Mexican literature, Mayo is founding editor of

Tameme Chapbooks ~ Cuadernos, and has also edited the anthology

Mexico: A Traveler's Literary Companion,

a portrait of Mexico in the fiction and literary prose of 24

Mexican writers.

Her other awards include three

Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Awards and three Washington Writing

Awards, most recently for her essay about a visit to Maximilian's

Italian castle, "From

Mexico to Miramar or, Across the Lake of Oblivion,"

published in the Massachusetts Review (also available

online at cmmayo.com/publications). Mayo currently divides her

time between Mexico City and Washington, D.C.

Interview

with the Author

You started writing with short fiction,

followed by your memoir of Baja California, Miraculous

Air. Did it serve as a transition into the novel, and

such a massive undertaking, at that? You started writing with short fiction,

followed by your memoir of Baja California, Miraculous

Air. Did it serve as a transition into the novel, and

such a massive undertaking, at that?

Definitely, especially with narrative

structure, a huge issue for me as a writer. Before the travel

memoir, I had written two books on finance, which helped me learn

how to structure a book length argument and, well, to just keep

plodding away at it! The travel memoir has a much more complex

structure, and then of course, the novel has an intriciate, even

labyrinthical structure. So with each book, I think I have progressed

in terms of mastering structure. At least I hope I have. And

of course Miraculous Air,

in recounting a series of journeys through "the Other Mexico"

that explores its independence from and connections to mainland

Mexico, is a kind of meditation on Mexico itself.

I wanted to ask you about

your decision to structure the novel by specific calendar days.

Was that an organic outcome of the creative process, or did those

dates correspond to historical events?

Yes,

in most cases they corresponded, but the structure of the novel

is that the opening three chapters, Book One, are set in a certain

time period but not on a particular day. The same can be said

of Book Three. Yes,

in most cases they corresponded, but the structure of the novel

is that the opening three chapters, Book One, are set in a certain

time period but not on a particular day. The same can be said

of Book Three.

But the bulk of the novel, the eighteen chapters that cromprise

Book Two, has a very different structure. Each chapter is set

on one specific date, beginning with "September 17, 1865:

The Prince Is in the Castle", when the secret contract between

Maximilian and the Iturbide family has begun, and ending with

"October 25, 1866: The Road to Orizaba", the date on

which Maximilian, in writing the letter releasing the child to

his parents, breaks the contract. In sum, Book Two is the life

of the contract, and though we have multiple flashbacks and flashforwards,

it has a linear, tick-tick-tick, structure.

But there is a second reason why each chapter corresponds to

one day: the novel not only has multiple points of view, it's

a transnational international story— we have the French

army, we have the Austrian aristocrats, we have Americans, we

have Mexicans, and Belgians, and Hungarians and Queen Victoria

and the Pope... it's complicated! And I realize, it would be

challenging beyond reason for the reader to follow who’s

who and what’s what without an anchor. That anchor is the

date.

And there is a third reason: to emphasize the long lags between

events and news of those events. In Mexico, for example, people

would learn about things that had happened in Europe weeks, even

months earlier. As the telegraph developed and the trans-Atlantic

Cable was laid in 1866, the the news speeded up. But compared

to our world, it was so very slow and affected—sometimes

tragically—some of the characters's decisions. This is a

recurring theme in the novel.

You have said that this novel

is about what it means, or meant to be, a Mexican. Could you

elaborate on that?

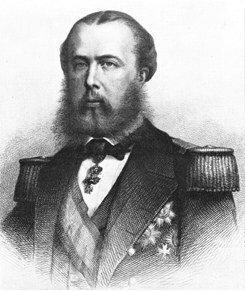

The

Second Empire was the assertion by the French, the Catholic Church,

and a group of Mexican conservatives that Mexicans should be

subjects. On the other hand, the Juarista response— ultimately

victorious— was that, no, Mexicans are citizens. Citizens

of a Republic. There is a fundamental difference between being

a subject and being a citizen. The former requires obedience

while the latter calls for participation. I could go on. But

more than that: Maximilian, for instance, genuinely saw himself

as Mexican, whereas any modern Mexican would probably roll their

eyes and huff, "how ridiculous!" Maximilian was an

Austrian aristocrat, imposed by a foreign army. Yet let's not

forget, in fact there were many Mexicans who welcomed and supported

him. The

Second Empire was the assertion by the French, the Catholic Church,

and a group of Mexican conservatives that Mexicans should be

subjects. On the other hand, the Juarista response— ultimately

victorious— was that, no, Mexicans are citizens. Citizens

of a Republic. There is a fundamental difference between being

a subject and being a citizen. The former requires obedience

while the latter calls for participation. I could go on. But

more than that: Maximilian, for instance, genuinely saw himself

as Mexican, whereas any modern Mexican would probably roll their

eyes and huff, "how ridiculous!" Maximilian was an

Austrian aristocrat, imposed by a foreign army. Yet let's not

forget, in fact there were many Mexicans who welcomed and supported

him.

So, what it is to be a Mexican is in part a cultural question,

but it’s also a political question, as in, "Who says?"

So if you’re a person from Czechoslovakia living in Mexico,

are you Mexican? In part that’s a legal question, depending

on your documents, and it’s also a cultural question. Modern

Mexico is incredibly diverse. I know of people who are 4th generation

Mexicans who have English names and consider themselves ethnically

English. We also have many indigenous peoples, some of whom who

don't speak Spanish. There are Russian and Polish Jews, a large

Lebanese community, Italians, French, Irish, Cubans, Guatemalans.

In recent years an increasing number of U.S. citizens have moved

down to Mexico and become naturalized Mexican citizens. In sum,

Mexico is more complex and diverse than many Americans perceive.

You have said that this very

brief, three year period, going on at the same time as our Civil

War, was a crucial turning point in Mexican history. How so?

This

is the story of the defeat of an idea: the monarchy. Today Mexicans

are not subjects but citizens. Let's not forget, one hundred

fifty years ago, the monarchical form of government, while not

universally, was widely accepted. This period in history is also

significant because, though Mexico has had a long history of

foreign invasions, and this was the ugliest of all. It was massive

and brutal, and though strenuous efforts, it was defeated. This

is why Cinco de Mayo, the commeoration of the battle of Puebla

on May 5, 1862, is so important to Mexicans. It was not a definitive

defeat of the French— only a temporary one, it turned out,

for the French regrouped and took Puebla a year later. However,

it was powerfully symbolic. That the rag-tag Army of the Republic

of Mexico could humiliate the French Imperial Forces, then considered

the greatest in the world, was no small thing. It was David slingshotting

Goliath: an international sensation. This

is the story of the defeat of an idea: the monarchy. Today Mexicans

are not subjects but citizens. Let's not forget, one hundred

fifty years ago, the monarchical form of government, while not

universally, was widely accepted. This period in history is also

significant because, though Mexico has had a long history of

foreign invasions, and this was the ugliest of all. It was massive

and brutal, and though strenuous efforts, it was defeated. This

is why Cinco de Mayo, the commeoration of the battle of Puebla

on May 5, 1862, is so important to Mexicans. It was not a definitive

defeat of the French— only a temporary one, it turned out,

for the French regrouped and took Puebla a year later. However,

it was powerfully symbolic. That the rag-tag Army of the Republic

of Mexico could humiliate the French Imperial Forces, then considered

the greatest in the world, was no small thing. It was David slingshotting

Goliath: an international sensation.

What about the issue of church

and state? Was that part of the Republican movement?

It

would be difficult to overstate the power of the Church in Mexico

at that time. Just in Mexico City, when you see how much real

estate they owned, nd how much money the Church had, it is really

jaw-dropping. And they also owned huge haciendas worked with

slaves. So that was a continuing is It

would be difficult to overstate the power of the Church in Mexico

at that time. Just in Mexico City, when you see how much real

estate they owned, nd how much money the Church had, it is really

jaw-dropping. And they also owned huge haciendas worked with

slaves. So that was a continuing is sue

throughout the 19th century in Mexico – how much power does

the church have, and how much the state? The Church supported

Maximilian and the French invasion in part because the Republicans

had confiscated Church property. It turned out, however, that

Maximilian did not reinstate the Church's properties. It just

wasn't feasible. But this remained a source of friction between

Maximilian and the Church. Another was that Maximilian was a

little too liberal for the Church; among other things the Church

objected to, he wanted to encourage immigration from ther ex-Confederacy

and from Europe, and he was willing to accept (gasp!) freedom

of worship for Protestants. In sum, though the Church supported

the Mexican Empire, it had its own interests and they did not

invariably align with Maximilian's. sue

throughout the 19th century in Mexico – how much power does

the church have, and how much the state? The Church supported

Maximilian and the French invasion in part because the Republicans

had confiscated Church property. It turned out, however, that

Maximilian did not reinstate the Church's properties. It just

wasn't feasible. But this remained a source of friction between

Maximilian and the Church. Another was that Maximilian was a

little too liberal for the Church; among other things the Church

objected to, he wanted to encourage immigration from ther ex-Confederacy

and from Europe, and he was willing to accept (gasp!) freedom

of worship for Protestants. In sum, though the Church supported

the Mexican Empire, it had its own interests and they did not

invariably align with Maximilian's.

Tell us about "falling

into the eggplant patch." This is a Mexican expression used

in the novel which might apply to your difficulties in researching

this novel.

On

its face, this is a confusing story. Why did Maximilian take

the little boy away from his parents and exile them? And why

did the parents, at least initially, agree to this? To answer

these questions we have to first, understand the social and political

context at the time, and second, get beyond our common understanding

of the meaning of a family. Many historians talk about Maximilian's

"adopting" the little boy, but that is not quite the

right word. On

its face, this is a confusing story. Why did Maximilian take

the little boy away from his parents and exile them? And why

did the parents, at least initially, agree to this? To answer

these questions we have to first, understand the social and political

context at the time, and second, get beyond our common understanding

of the meaning of a family. Many historians talk about Maximilian's

"adopting" the little boy, but that is not quite the

right word.

Maximilian understood it as more or less analogous to the relationship

between Louis Napolean, the Emperor of France, and the Murat

Princes. And in this day and age, for heavensakes, who remembers

the Murat princes?! But if you don’t know who they were,

it’s very difficult to understand what Maximilian was thinking.

Basically what he was saying was, I grant the Iturbides the

status of Highnesses and as such they join my house. So he

did not think of the child as his own but rather as a kind of

cousin— a member of an extended family under his leadership

and protection. It’s that concept that’s very difficult

to understand with a 20th-21st century mentality. And to add

to the confusion, many people who were close to Maximilian at

the time were themselves quite flummoxed.

The

second reason why it was difficult to tell the story is that

the period itself is incredibly complex. In fact we cannot consider

it "Mexican" history so much as it is transnational

history. Why did French invade Mexico? Why did the Church support

this? Why did the Kaiser of Austria allow his younger brother

go? Who was Maximilian's wife, the Empress Carlota? She was the

Princess of Belgium and the first cousin of Queen Victoria. And

both King Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria had plenty

to say about Mexico. England had many important businesses in

mining and textiles and so on, so the British Ambassador was

an important figure in Mexico, and in any event, what Queen Victoria

thought of all this was vital to all concerned. And of course

the United States were scheming to get the French out of Mexico,

plus there was the business of the Confederacy and its relationship

to Mexico. So it was an extraordinarily complex period. The

second reason why it was difficult to tell the story is that

the period itself is incredibly complex. In fact we cannot consider

it "Mexican" history so much as it is transnational

history. Why did French invade Mexico? Why did the Church support

this? Why did the Kaiser of Austria allow his younger brother

go? Who was Maximilian's wife, the Empress Carlota? She was the

Princess of Belgium and the first cousin of Queen Victoria. And

both King Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria had plenty

to say about Mexico. England had many important businesses in

mining and textiles and so on, so the British Ambassador was

an important figure in Mexico, and in any event, what Queen Victoria

thought of all this was vital to all concerned. And of course

the United States were scheming to get the French out of Mexico,

plus there was the business of the Confederacy and its relationship

to Mexico. So it was an extraordinarily complex period.

A third reason: for many Mexicans

the period is politically embarrassing. It’s easier to say,

well, these were foreign invaders, and we repelled them –

a truth that is not the whole big, messy, and oh-so human truth.

To take one of many examples, there is a museum in Mexico City

of the Mexican equivalent of the Secret Service. But are there

photos, uniforms, or arms of any of Maximilian's Palatine Guards

in there? Not on your life! So you see, there are many stories

that have been hidden or buried.

Finally: when I looked at the

main works on the Second Empire what I found about the little

prince, Maximilian's the arrangement with the Iturbides, was

really peculiar. In the memoirs of those who had been close to

Maximilian or in Mexico City society at the time, the affair

was barely mentioned, or garbled in the strangest ways. For example,

Sara Yorke Stevenson's otherwise excellent memoir crammed the

whole story of the prince into a brief footnote near the end.

I found this especially strange because she would have known

the family socially, and she knew General Bazaine.

The Juarista versions of things one has to take with a truck-load

of salt – let's not forget, they were at war with the Empire,

and they did not hesitate to use malicious rumors as weapons

(for example, that Maximilian supposedly had syphilis). Also,

various memoirists claim that the father of the prince was dead

or that the mother had been been married to someone else or that

the child was older—all wrong. It was as if there was this

matter those close to the court just didn't want to acknowledge—there

was some sort of cognitive dissonance going on. The affair with

the Iturbides was of course, a painful embarrassment for both

Maximilian and Carlota, both personally and politically.

You had to research this novel

all over the world, for several years, just to put the story

together. At what point did you start writing, creating scenes,

"hearing voices" so to speak as characters became real

to you?

After

a few years of flailing about, the novel suddenly started coming

together with "November 23, 1865: The Charm of Her Existence,"

the chapter now in the middle of the novel when Alicia goes to

Paris, and appeals to John Bigelow, the U.S. ambassador to France,

for help. It's written in John Bigelow's point of view. I was

only able to write this chapter after delving into his papers

at the New York Public Library. After

a few years of flailing about, the novel suddenly started coming

together with "November 23, 1865: The Charm of Her Existence,"

the chapter now in the middle of the novel when Alicia goes to

Paris, and appeals to John Bigelow, the U.S. ambassador to France,

for help. It's written in John Bigelow's point of view. I was

only able to write this chapter after delving into his papers

at the New York Public Library.

It took me a while to realize that there is no single character

that can carry the novel; by necessity, it had to be written

in multiple points of view. The novel has this Roshomon quality,

that is, we go back and see the same story— Alice, frantic

with grief, returning for her child and instead of finding compassion,

she ends up under arrest– from various points of view, each

one a completely different lens, a very different interpretation.

Bigelow's couldn't be more different than Maximilian's, or say,

Frau von Kuhacsevich's or Princess (Pepa) Iturbide's or, for

that matter, a vacationing Prussian count's or the Scottish bookshop

owner's in Paris.

Writing this chapter from Bieglow's point of view was so liberating:

oh, you know, I can do this!

But about the multiple points

of view. Usually when you see multiple points of view it means

that the author has lost control of the narrative, or doesn’t

know what she is doing. The author is asking a lot of the reader

when she uses multiple points of view. But what I realized was

that the main character, the last prince of the Mexican Empire,

is not a person so much as an idea, the living symbol of the

future of the Mexican Empire.

As for hearing voices, yes, that

happens at all points. It's startling sometimes, but also quite

normal when writing fiction. I don't hear voices as if they were

coming out of a radio; rather, a sort of vague nudge, like remembering

a line of dialogue.

So it sounds like you did

start work on the novel before finishing the research.

Yes,

and in fact, I had a complete draft of the novel when I suddenly

realized that of course, the educated people of that time and

particularly Maximilian would have seen everything through the

lens of classical antiquity. I hadn't emphasized quite as much

as I should have, so I brought in some more Tacitus and Cicero

and Augustus, and so on. And even as the book was in its final

stages, I was able to splice in some bits and pieces (and corrections)

thanks to Dr Konrad Ratz's splendid and very recently published

work on Maximilian, Tras las huellas de un desconocido

(In the footsteps of an unknown), which relies heavily on his

original translations from various German language documents. Yes,

and in fact, I had a complete draft of the novel when I suddenly

realized that of course, the educated people of that time and

particularly Maximilian would have seen everything through the

lens of classical antiquity. I hadn't emphasized quite as much

as I should have, so I brought in some more Tacitus and Cicero

and Augustus, and so on. And even as the book was in its final

stages, I was able to splice in some bits and pieces (and corrections)

thanks to Dr Konrad Ratz's splendid and very recently published

work on Maximilian, Tras las huellas de un desconocido

(In the footsteps of an unknown), which relies heavily on his

original translations from various German language documents.

I should note that Dr Ratz' also

translated and edited a collection of letters between Maximilian

and Carlota. Anyone who reads these letters will see that their

relationship was very different than that painted in most of

the histories. To be sure, their relationship had its challenges,

but Maximilian and Carlota did deeply love and respect one another.

With so many letters over such a long period, this becomes clear.

But what was going on between

them? The novel is full of gossip and rumors, and at one point,

there is the blatant suggestion that Maximilian was homosexual.

And we learn that Maximilian and Carlota do not have a physical

relationship, much to Carlota’s frustration. Or was he asexual?

The answer I prefer is that we

will never know. When you work as a novelist, you try to put

yourself into the place of your characters and imagine what it

must have been like for them. In that spirit, I do think it is

pertinent to note how young they were (he was in his very early

thirties, she was only 25), and how intense the pressure they

were under, constantly, with never a moment of privacy, ever.

They were in great danger; there were assassination attempts.

People around them died of yellow fever, a kind of hemorragic

fever, one of the most ghastly ways to die. And add to that the

fact that Maximilian was plagued with diahrrea, pains in the

liver, fevers, malaria. And as everything began to collapse around

them, they were both suffering unbelievable stress. His health

collapsed and, famously, while visiting the Pope in the Vatican

in 1866, Carlota had a psychotic breakdown from which she never

recovered. Well, but going back to the times in Mexico: this

sort of pressure would have dampened anyone's interest in sex,

no?

But the fact is that

Maximilian and Carlota had been married for several years before

they came to Mexico, and apparently they thought they never would

have children. In the novel, Alice, the mother of the prince,

has her pet theories– which by the way, are based on an

actual interview she gave to Bigelow when he visited Mexico City

in 1882. For those who haven't yet read the novel, I don't want

to give it away here, but I will say, it's spicey! And she's

a source much closer than most. That said, who knows? There is

endless gossip. People will believe what they want to believe.

The whole novel has this house-of-mirrors quality. That was my

intent.

I know that John Bigelow is

one of your favorite characters, but how about the whole cast?

Do you have personal feelings about them one way or the other

at this point?

Alice / Alicia was not an easy character;

in my first drafts I was too hard on her. It's easy to condemn

her for giving up her son to Maximilian, but who hasn't been

"a little dazzled maybe," as she put it, about it something,

some time? She had a both adventurous and tenacious spirit and

yet, she was so young and naive. Also, she was under enormous

pressure from a very powerful personality: her older sister-in-law,

who had a great deal to gain from the arrangement with Maximilian.

Maximilian, well, over the years, I feel I made enormous strides

in trying to understand him, but at some level I've lost patience

with him. He was so wrapped up in appearances. You can see that

in his handwriting. And by the way, I did go to books on graphology

to try and understand many of these characters, because my research

was all with handwritten documents. While Alice's handwriting

is forward-slanting, spikey, rhythmic, Maximilian's looks almost

like Arab caligraphy with all these sweeping backward loops.

It's gorgeous, but it must have taken him twice the time it would

take anyone else to write anything! Though his less formal notes

devolve into something rather like Alice's handwriting, now that

I think about it.. Angelo's handwriting was over-large; Carlota's

(before her break down) rigidly neat. Alice / Alicia was not an easy character;

in my first drafts I was too hard on her. It's easy to condemn

her for giving up her son to Maximilian, but who hasn't been

"a little dazzled maybe," as she put it, about it something,

some time? She had a both adventurous and tenacious spirit and

yet, she was so young and naive. Also, she was under enormous

pressure from a very powerful personality: her older sister-in-law,

who had a great deal to gain from the arrangement with Maximilian.

Maximilian, well, over the years, I feel I made enormous strides

in trying to understand him, but at some level I've lost patience

with him. He was so wrapped up in appearances. You can see that

in his handwriting. And by the way, I did go to books on graphology

to try and understand many of these characters, because my research

was all with handwritten documents. While Alice's handwriting

is forward-slanting, spikey, rhythmic, Maximilian's looks almost

like Arab caligraphy with all these sweeping backward loops.

It's gorgeous, but it must have taken him twice the time it would

take anyone else to write anything! Though his less formal notes

devolve into something rather like Alice's handwriting, now that

I think about it.. Angelo's handwriting was over-large; Carlota's

(before her break down) rigidly neat.

I had a lot of fun with the minor

characters. Frau von Kuhacsevich is just the total id, you know?

And Baron d'Huart at once so petulant and sunny, always alert

to beauty and flavor... Lupe the runaway nanny, this sort of

lost lamb. In sum, I feel affection for all of the characters;

there is a little piece of me in all of them. That is part of

the fun of writing a novel. You have to ask yourself, have I

ever felt that way? Maybe you don’t approve of a person

who felt that way, but have you ever, even just a little bit,

felt that way yourself?

When you have been asked why,

after all this research, you decided to write this story as fiction,

you have said that you wanted to tell an emotional truth. Could

you elaborate on that?

Why Maximilian and Carlota came

to Mexico, why Maximilian took the Iturbide child and why the

Iturbides agreed to sign his contract are all questions impossible

to answer without an understanding of their personalities and

motives. Put another way, these are all matters of character

and emotions, and for this kind of exploration the novel, as

a form, is unsurpassed. I think of the form as a kind of vivid

dream or, to use a more modern term, "virtual reality"—

it allows you to experience what it would be like to, say, come

into the parlor and sip ginger tea and pass around a carte-de-visite;

dance at a ball; push through a cheering crowd; smell of the

razorsharp air in a pine forest. And this very vividness is what

invites people, I hope, to feel more empathy with the people

in this time, this place, and caught in these situations.

I’m not saying I want the reader to approve of any of this,

but to come into the experience of it, and so understand it all

a little better.

Put another way, the novelist has more tools to engage the reader.

One of the tools you use to

engage the reader is with the upstairs downstairs interplay.

You say that you researched these people sociologically—the nurses, the bodyguards,

the cooks—but that they are made up. How did this

interplay help you to tell an emotional truth?

Once I realized that this was

a novel about an idea—the last prince not as a person but

as the living symbol of the future of the Empire— and that

therefore it had to be told from multiple points of view, I realized

that I had to have some character or characters, beyond John

Bigelow, who were opposed to Maximilian. And I didn’t want

to go to a higher level, someone like President Benito Juárez

himself, because that would have made the novel unmanageably

big. But I needed a Mexican character who was opposed to the

empire and who was, in some way, going to interact with the other

characters. And it made sense that it might be someone who was

working as a guerilla, who might be a bandit, and the wonderful

thing of making him a bandit is that I could have him take on

the nanny, who runs off when the Iturbides leave Mexico City.

Another wonderful thing about choosing a bandit is that I could

take the action to Rio Frio, a place on the highway in the mountains

between Mexico City and Puebla where bandits often attacked the

stagecoaches.

A true and absolutely devastating embarrassment for Maximilian—

mentioned in all the histories of the empire—was the murder

of Baron Frédéric Victor d'Huart, the Belgian envoy

and close friend of Carlota's brother of the Duke of Flanders,

at Rio Frio. This story is told in the chapter "March 4,

1866: Río Frío" and (in Maximilian's flashbacks)

"July 10, 1866: One Stays the Course".

Why do you think we in the

United States are generally so ignorant about our immediate neighbor

to the South?

There are constellations of reasons,

and everyone, including our most celebrated PhDs in Mexican Whatever,

is to some degree ignorant, for no one can know everything! But

I prefer to flip the question and ask, why are people in other

countries so ignorant about the United States? Is it arrogance?

Laziness? Cowardice? Other prioirities? Cognitive dissonance?

This is a many-faceted question and for each individual at each

moment in time, the answer can change.

So, coming back to Mexico, The

Last Prince of the Mexican Empire is a story to open

your mind, however closed, however open it may already be. Come

in and hear all about it!

What are some of the things you want the reader who accepts your

invitation "to come on in and hear all about it" to

discover?

First, that the prince's mother was not

only an American, but an American from very prominent family

in Washington society—the aristocracy of her time and place.

She was the granddaughter of the Revolutionary War General Uriah

Forrest and she was also descended from Maryland's Governor Plater,

major figures in their time. So it shouldn't be a surprise that

she had the wherewithal to get up what was truly an international

scandal over Maximilian's refusal to return her child. First, that the prince's mother was not

only an American, but an American from very prominent family

in Washington society—the aristocracy of her time and place.

She was the granddaughter of the Revolutionary War General Uriah

Forrest and she was also descended from Maryland's Governor Plater,

major figures in their time. So it shouldn't be a surprise that

she had the wherewithal to get up what was truly an international

scandal over Maximilian's refusal to return her child.

And though his novel takes place mostly in Mexico and in Europe,

this is very much an American story. It was only with the U.S.

embroiled din its own Civil War that France dared to invade Mexico.

And later, after the Confederates surrender, without the support

of the United States, it would have been a far tougher battle

for the Juaristas to retake Mexico.

Second, this is a story of foreign

intervention. I was working on this novel when our government

invaded Iraq, and most of the people opposed to this brought

up the specter of Vietnam. But it seems to me that a more apt

comparison would have been to the French in Mexico which, alas,

most Americans know little if anything about.

Finally, this is a novel about

compassion and forgiveness.

If there is any one thing that you want the reader to take away

from this novel, what would that be?

That there are infinite layers

of complexity. And that every time we hold a candle to the past,

we also illuminate the present.

Questions

for Discussion

What was your immediate

response to this novel? Have you ever visited Mexico? How much

about Mexico did you know, or think you knew, before reading

this novel? How and in what ways did this novel add to or change

your impressions and knowledge of Mexican history and culture?

How would you describe

the tone and style of this novel? What did you enjoy most about

the novel?

Do you agree with the

author’s decision to tell this story as fiction? Discuss

the pros and cons of her reasons for doing so, including her

contention that novelists are, or should be, "armchair sociologists."

What do you think she means by that? What do you think she means

by wanting to tell "an emotional truth?"

The author says that

the main character of the novel is an Idea – the Idea being

the future of Empire in Mexico, so she had to tell it from multiple

points of view, which she thinks is asking a lot of the reader.

Did you find that to be so? How satisfied were you with her structure

of organizing Book Two of the novel around dates delineating

the life of the contract between the Iturbides and Maximilian?

Do you think she succeeded in making the multiple points of view

easier for readers to follow by using that structure?

Discuss the way the

author uses gossip and rumor (all of which is historically accurate,

from her meticulous research) to tell her story. What do you

think she wants the reader to conclude from its use?

Who are your favorite

characters in the novel? Why? Which ones are the most interesting

to you, and why? How and why, or why not, did you identify with

any of them? Why do you suppose the author would say that there

were things about Alicia that she could relate to?

What were your initial

impressions, or opinions about, Maximilian and Carlota? If they

changed or evolved as the novel progressed, identify and discuss

one or more scenes from the novel that changed your point of

view about them. Do the same exercise for Alicia and Angelo Iturbide,

and Pepa.

Why do you think the

Iturbides entered into the contract with Maximilian to grant

him custody of their son, Augustin? Discuss from the points of

view of all members of the family. Why do you think Maximilian

and Carlota wanted to take custody of him?

When the author describes

this novel as "an American story," what does that mean

to you? Do you agree with her? Why, or why not, as the case may

be?

If you could talk with

the author, what are some questions that are unanswered in Book

Three and the Epilogue you would want to ask her about?

This novel is remarkable

in its attention to the accurate, historical detail of daily

life—how people dressed, what they ate, where

they lived, how they entertained, how the table was set for a

state dinner, the protocol for lunch, the social structure in

a bandit’s lair, and more, much like the HBO mini-series,

John Adams. If you were producing a movie or mini-series version

of this novel, who would you cast in the major roles?

Recommended

Reading

"From

Mexico to Miramar or, Across the Road to Oblivion,"

by C. M. Mayo (see above for source)

The War of the End

of the World,

by Mario Vargas Llosa

Woe to Live On, by Daniel Woodrell (alternate

title: Ride with the Devil).

A Flag for Sunrise, by Robert Stone

Nostromo, by Joseph Conrad

The Bandits of Rio

Frio, by Manuel

Payno, translated by Alan Fluckey

Hallem’s War, by Elizabeth Payne Rosen

The Hummingbird’s

Daughter, by

Luis Alberto Urrea

The Leopard, by Guiseppe di Lampedusa

Open Veins of Latin

America, by

Eduardo Galeano, with a forward by Isabel Allende

John Adams, a seven part HBO mini-series,

available on DVD, based upon David McCollough’s Pulitzer

Prize winning book of the same name.

>More

information for book groups.***

"Mayo's reanimation

of a crucial period in Mexican history should satisfy history

buffs and those in the mood for an engaging story brimming with

majestic ambition.

Publisher's

Weekly

"a swashbuckling, riotous good time, befitting the fairy-tale

promise of the opening sentence"

Austin

American-Statesman

"Mayo’s cultural insights are first-rate, and the glittering,

doomed regime comes to life"

Library

Journal (Xpress Review)

"I have read a few sweeping historical novels that have

remain inside of me forever. Tolstoy's War and Peace is

one of those, Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities is another,

Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago is another, and now The

Last Prince of the Mexican Empire is another."

Mexico

Connect |

Tulpa

Max or, Notes on the Afterlife of a Resurrection

Catamaran Literary Reader, summer 2017. Also published in Spanish

in Letras Libres.

On Seeing as an Artist or, Five Techniques for a Journey to Einfühlung

Transcript of my remarks for the panel on "Writing Across

Borders and Cultures" Women Writing the West Conference,

Santa Fe, New Mexico, October 15, 2016

C.M.

Mayo at the Library of Congress

A

presentation of the the novel, The

Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, and an overview of

the author's research in the various archives in the Library

of Congress, among them, the papers of the Iturbide family, the

Emperor Iturbide, and the circa 1920 copies of a substantial

portion of the Kaiser Maximilian von Mexiko archive in Vienna.

The lecture was sponsored by the Hispanic Division of the Library

of Congress, which is the center for the study of the cultures

and societies of Latin America, the Caribbean, the Iberian Peninsula

and the Spanish Borderlands, and other areas with Spanish and

Portuguese influence. Recorded live July 20, 2009. A

presentation of the the novel, The

Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, and an overview of

the author's research in the various archives in the Library

of Congress, among them, the papers of the Iturbide family, the

Emperor Iturbide, and the circa 1920 copies of a substantial

portion of the Kaiser Maximilian von Mexiko archive in Vienna.

The lecture was sponsored by the Hispanic Division of the Library

of Congress, which is the center for the study of the cultures

and societies of Latin America, the Caribbean, the Iberian Peninsula

and the Spanish Borderlands, and other areas with Spanish and

Portuguese influence. Recorded live July 20, 2009.

(APPROX

1 HOUR)

The Book Studio

Bethanne Patrick

("The Book Maven") interviews C.M. Mayo about The

Last Prince of the Mexican Empire and

the Washington DC story behind the story. January 22, 2010.

Connections

Literary Magazine: "The Politics of Love"

Mary J. Lohnes interviews

C.M. Mayo about The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire. October

2010.

Jenn's

Bookshelves Blog

Interview by Jenn about The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire.

November 12, 2010.

Historicalnovels.info

An

interview by historical novels blogger Margaret Donsbach. October

20, 2010.

Latina

Book Club

Maria

Ferrer's NYC-based blog, embracing Hispanic heritage. September

15, 2010.

El Calendario de Todos Santos El Calendario de Todos Santos

Writer Michael Mercer

interviews C.M. Mayo about the writing of The Lasst Prince

of the Mexican Empire. March 2010

Coffee

with a Canine Blog

Interview by Marshal

Zeringue. November 25, 2009.

Critical

Mass: National Book Critics Circle

Small Press Spotlight:

An Interview with C.M. Mayo by Rigoberto Gonzalez. October 11,

2009.

Fall for the Book Festival (George Mason University): David

Heath interviews C.M. Mayo about The Last Prince of the Mexican

Empire and the story behind the story of Mexico's half-American

prince. September 2009. (To read the complete interview, which

includes previously unpublished Q & A about the Empress Carlota,

click

here.)

Amigos

de la Universidad de Chicago

(University of Chicago Mexico Alumni Association)

Apropos of the presentation

of The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire in Mexico City

September 2009.

Click

here for photos of the event. Click

here for photos of the event.

Write

On! Online

Debra Eckerling

interviews C.M. Mayo about The Last Prince of the Mexican

Empire and the writing process. July 3, 2009.

Largehearted

Boy Largehearted

Boy

A guest-blog post with a playlist for The Last Prince of the

Mexican Empire.

Savvy Verse & Wit Interview by leading book blogger Serena

Agusto-Cox about The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire.

Whereabouts

Press Blog

John

Bennett interviews C.M. Mayo about The Last Prince of the

Mexican Empire— and some of the stories

(by Araceli Ardón, Fernando del Paso,

Mónica Lavín) in Mexico: A Traveler's

Literary Companion.

Ten

Questions for C.M. Mayo

Writerly interview

by Wendy Burt March 1, 2009.

More interviews More interviews

Many of the more recent interviews about later books also discuss

The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire and Mexican history.

A few guest-blogs and comments:

What Connects

You to the 1860s?

The

Top 5 of the Tussie-Mussie

About

the Jamesian Roving Intelligence

More

on the research behind this book More

on the research behind this book

Contact

C.M. Mayo Contact

C.M. Mayo

|

The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire

The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire on

a life of its own, and the story of two heartbroken parents trying

to get their little boy back from a callous pair of Royals growing

more unstable by the day as the French withdraw from Mexico and

their Second Empire comes crashing down around them, grew into

something much larger: an international story of political intrigue,

war and diplomacy that plays out in Mexico City,

on

a life of its own, and the story of two heartbroken parents trying

to get their little boy back from a callous pair of Royals growing

more unstable by the day as the French withdraw from Mexico and

their Second Empire comes crashing down around them, grew into

something much larger: an international story of political intrigue,

war and diplomacy that plays out in Mexico City,

Yes,

in most cases they corresponded, but the structure of the novel

is that the opening three chapters, Book One, are set in a certain

time period but not on a particular day. The same can be said

of Book Three.

Yes,

in most cases they corresponded, but the structure of the novel

is that the opening three chapters, Book One, are set in a certain

time period but not on a particular day. The same can be said

of Book Three.  The

Second Empire was the assertion by the French, the Catholic Church,

and a group of Mexican conservatives that Mexicans should be

subjects. On the other hand, the Juarista response— ultimately

victorious— was that, no, Mexicans are citizens. Citizens

of a Republic. There is a fundamental difference between being

a subject and being a citizen. The former requires obedience

while the latter calls for participation. I could go on. But

more than that: Maximilian, for instance, genuinely saw himself

as Mexican, whereas any modern Mexican would probably roll their

eyes and huff, "how ridiculous!" Maximilian was an

Austrian aristocrat, imposed by a foreign army. Yet let's not

forget, in fact there were many Mexicans who welcomed and supported

him.

The

Second Empire was the assertion by the French, the Catholic Church,

and a group of Mexican conservatives that Mexicans should be

subjects. On the other hand, the Juarista response— ultimately

victorious— was that, no, Mexicans are citizens. Citizens

of a Republic. There is a fundamental difference between being

a subject and being a citizen. The former requires obedience

while the latter calls for participation. I could go on. But

more than that: Maximilian, for instance, genuinely saw himself

as Mexican, whereas any modern Mexican would probably roll their

eyes and huff, "how ridiculous!" Maximilian was an

Austrian aristocrat, imposed by a foreign army. Yet let's not

forget, in fact there were many Mexicans who welcomed and supported

him.  This

is the story of the defeat of an idea: the monarchy. Today Mexicans

are not subjects but citizens. Let's not forget, one hundred

fifty years ago, the monarchical form of government, while not

universally, was widely accepted. This period in history is also

significant because, though Mexico has had a long history of

foreign invasions, and this was the ugliest of all. It was massive

and brutal, and though strenuous efforts, it was defeated. This

is why Cinco de Mayo, the commeoration of the battle of Puebla

on May 5, 1862, is so important to Mexicans. It was not a definitive

defeat of the French— only a temporary one, it turned out,

for the French regrouped and took Puebla a year later. However,

it was powerfully symbolic. That the rag-tag Army of the Republic

of Mexico could humiliate the French Imperial Forces, then considered

the greatest in the world, was no small thing. It was David slingshotting

Goliath: an international sensation.

This

is the story of the defeat of an idea: the monarchy. Today Mexicans

are not subjects but citizens. Let's not forget, one hundred

fifty years ago, the monarchical form of government, while not

universally, was widely accepted. This period in history is also

significant because, though Mexico has had a long history of

foreign invasions, and this was the ugliest of all. It was massive

and brutal, and though strenuous efforts, it was defeated. This

is why Cinco de Mayo, the commeoration of the battle of Puebla

on May 5, 1862, is so important to Mexicans. It was not a definitive

defeat of the French— only a temporary one, it turned out,

for the French regrouped and took Puebla a year later. However,

it was powerfully symbolic. That the rag-tag Army of the Republic

of Mexico could humiliate the French Imperial Forces, then considered

the greatest in the world, was no small thing. It was David slingshotting

Goliath: an international sensation. It

would be difficult to overstate the power of the Church in Mexico

at that time. Just in Mexico City, when you see how much real

estate they owned, nd how much money the Church had, it is really

jaw-dropping. And they also owned huge haciendas worked with

slaves. So that was a continuing is

It

would be difficult to overstate the power of the Church in Mexico

at that time. Just in Mexico City, when you see how much real

estate they owned, nd how much money the Church had, it is really

jaw-dropping. And they also owned huge haciendas worked with

slaves. So that was a continuing is sue

throughout the 19th century in Mexico – how much power does

the church have, and how much the state? The Church supported

Maximilian and the French invasion in part because the Republicans

had confiscated Church property. It turned out, however, that

Maximilian did not reinstate the Church's properties. It just

wasn't feasible. But this remained a source of friction between

Maximilian and the Church. Another was that Maximilian was a

little too liberal for the Church; among other things the Church

objected to, he wanted to encourage immigration from ther ex-Confederacy

and from Europe, and he was willing to accept (gasp!) freedom

of worship for Protestants. In sum, though the Church supported

the Mexican Empire, it had its own interests and they did not

invariably align with Maximilian's.

sue

throughout the 19th century in Mexico – how much power does

the church have, and how much the state? The Church supported

Maximilian and the French invasion in part because the Republicans

had confiscated Church property. It turned out, however, that

Maximilian did not reinstate the Church's properties. It just

wasn't feasible. But this remained a source of friction between

Maximilian and the Church. Another was that Maximilian was a

little too liberal for the Church; among other things the Church

objected to, he wanted to encourage immigration from ther ex-Confederacy

and from Europe, and he was willing to accept (gasp!) freedom

of worship for Protestants. In sum, though the Church supported

the Mexican Empire, it had its own interests and they did not

invariably align with Maximilian's. On

its face, this is a confusing story. Why did Maximilian take

the little boy away from his parents and exile them? And why

did the parents, at least initially, agree to this? To answer

these questions we have to first, understand the social and political

context at the time, and second, get beyond our common understanding

of the meaning of a family. Many historians talk about Maximilian's

"adopting" the little boy, but that is not quite the

right word.

On

its face, this is a confusing story. Why did Maximilian take

the little boy away from his parents and exile them? And why

did the parents, at least initially, agree to this? To answer

these questions we have to first, understand the social and political

context at the time, and second, get beyond our common understanding

of the meaning of a family. Many historians talk about Maximilian's

"adopting" the little boy, but that is not quite the

right word.  The

second reason why it was difficult to tell the story is that

the period itself is incredibly complex. In fact we cannot consider

it "Mexican" history so much as it is transnational

history. Why did French invade Mexico? Why did the Church support

this? Why did the Kaiser of Austria allow his younger brother

go? Who was Maximilian's wife, the Empress Carlota? She was the

Princess of Belgium and the first cousin of Queen Victoria. And

both King Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria had plenty

to say about Mexico. England had many important businesses in

mining and textiles and so on, so the British Ambassador was

an important figure in Mexico, and in any event, what Queen Victoria

thought of all this was vital to all concerned. And of course

the United States were scheming to get the French out of Mexico,

plus there was the business of the Confederacy and its relationship

to Mexico. So it was an extraordinarily complex period.

The

second reason why it was difficult to tell the story is that

the period itself is incredibly complex. In fact we cannot consider

it "Mexican" history so much as it is transnational

history. Why did French invade Mexico? Why did the Church support

this? Why did the Kaiser of Austria allow his younger brother

go? Who was Maximilian's wife, the Empress Carlota? She was the

Princess of Belgium and the first cousin of Queen Victoria. And

both King Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria had plenty

to say about Mexico. England had many important businesses in

mining and textiles and so on, so the British Ambassador was

an important figure in Mexico, and in any event, what Queen Victoria

thought of all this was vital to all concerned. And of course

the United States were scheming to get the French out of Mexico,

plus there was the business of the Confederacy and its relationship

to Mexico. So it was an extraordinarily complex period. After

a few years of flailing about, the novel suddenly started coming

together with "November 23, 1865: The Charm of Her Existence,"

the chapter now in the middle of the novel when Alicia goes to

Paris, and appeals to John Bigelow, the U.S. ambassador to France,

for help. It's written in John Bigelow's point of view. I was

only able to write this chapter after delving into his papers

at the New York Public Library.

After

a few years of flailing about, the novel suddenly started coming

together with "November 23, 1865: The Charm of Her Existence,"

the chapter now in the middle of the novel when Alicia goes to

Paris, and appeals to John Bigelow, the U.S. ambassador to France,

for help. It's written in John Bigelow's point of view. I was

only able to write this chapter after delving into his papers

at the New York Public Library.  Yes,

and in fact, I had a complete draft of the novel when I suddenly

realized that of course, the educated people of that time and

particularly Maximilian would have seen everything through the

lens of classical antiquity. I hadn't emphasized quite as much

as I should have, so I brought in some more Tacitus and Cicero

and Augustus, and so on. And even as the book was in its final

stages, I was able to splice in some bits and pieces (and corrections)

thanks to Dr Konrad Ratz's splendid and very recently published

work on Maximilian, Tras las huellas de un desconocido

(In the footsteps of an unknown), which relies heavily on his

original translations from various German language documents.

Yes,

and in fact, I had a complete draft of the novel when I suddenly

realized that of course, the educated people of that time and

particularly Maximilian would have seen everything through the

lens of classical antiquity. I hadn't emphasized quite as much

as I should have, so I brought in some more Tacitus and Cicero

and Augustus, and so on. And even as the book was in its final

stages, I was able to splice in some bits and pieces (and corrections)

thanks to Dr Konrad Ratz's splendid and very recently published

work on Maximilian, Tras las huellas de un desconocido

(In the footsteps of an unknown), which relies heavily on his

original translations from various German language documents.

Alice / Alicia was not an easy character;

in my first drafts I was too hard on her. It's easy to condemn

her for giving up her son to Maximilian, but who hasn't been

"a little dazzled maybe," as she put it, about it something,

some time? She had a both adventurous and tenacious spirit and

yet, she was so young and naive. Also, she was under enormous

pressure from a very powerful personality: her older sister-in-law,

who had a great deal to gain from the arrangement with Maximilian.

Maximilian, well, over the years, I feel I made enormous strides

in trying to understand him, but at some level I've lost patience

with him. He was so wrapped up in appearances. You can see that

in his handwriting. And by the way, I did go to books on graphology

to try and understand many of these characters, because my research

was all with handwritten documents. While Alice's handwriting

is forward-slanting, spikey, rhythmic, Maximilian's looks almost

like Arab caligraphy with all these sweeping backward loops.

It's gorgeous, but it must have taken him twice the time it would

take anyone else to write anything! Though his less formal notes

devolve into something rather like Alice's handwriting, now that

I think about it.. Angelo's handwriting was over-large; Carlota's

(before her break down) rigidly neat.

Alice / Alicia was not an easy character;

in my first drafts I was too hard on her. It's easy to condemn

her for giving up her son to Maximilian, but who hasn't been

"a little dazzled maybe," as she put it, about it something,

some time? She had a both adventurous and tenacious spirit and

yet, she was so young and naive. Also, she was under enormous

pressure from a very powerful personality: her older sister-in-law,

who had a great deal to gain from the arrangement with Maximilian.

Maximilian, well, over the years, I feel I made enormous strides

in trying to understand him, but at some level I've lost patience

with him. He was so wrapped up in appearances. You can see that

in his handwriting. And by the way, I did go to books on graphology

to try and understand many of these characters, because my research

was all with handwritten documents. While Alice's handwriting

is forward-slanting, spikey, rhythmic, Maximilian's looks almost

like Arab caligraphy with all these sweeping backward loops.

It's gorgeous, but it must have taken him twice the time it would

take anyone else to write anything! Though his less formal notes

devolve into something rather like Alice's handwriting, now that

I think about it.. Angelo's handwriting was over-large; Carlota's

(before her break down) rigidly neat.

El Calendario de Todos Santos

El Calendario de Todos Santos

Largehearted

Boy

Largehearted

Boy